Mr K asked: "Hi, I've enjoyed reading the blog. I was wondering where your course of study has led you to now? I've been exploring Dzogchen lately and plan to do so for the next couple months before digging into Mahamudra, and then seeing what resonates best for me.

I was curious if you've found yourself studying with a particular teacher, or if a particular teacher did the best job of pointing out and confirming the nature of mind for you, and then how to rest in it (or if they were different).

Thanks for sharing your experiences!"

Soh replied:

Hi Mr K,

Thanks so much for reading the blog and for your thoughtful note. I’m glad you’re exploring Dzogchen now and considering Mahāmudrā next—that’s a great way to taste both streams and see what resonates.

Where my study led me (and who pointed out mind’s nature for me)

My main teacher is John Tan. He taught me early on, led to my realization of mind’s nature, and I continue to learn from him. I also have an interest in Dzogchen, and have attended teachings by Ācārya Malcolm Smith in recent years.

Nature of mind is nature of mind—the same recognition in Zen/Chan, Mahāmudrā, or Dzogchen.

To underscore that unity, here are two comments by Ācārya Malcolm Smith (from DharmaWheel) quoted verbatim:

"There really is no difference between perfection of wisdom, mahāmudra, Chan/Zen, etc., and tregchöd. I have heard it said that Tulku Orgyen asserted that trekchöd exists in all yānas, perhaps EPK would be kind enough to confirm this. What separates from trekchöd from these other systems of the method of introduction. Trekchöd, like any secret mantra practice, is based on empowerment/introduction."

"Realization of Chan, Mahāmudra, and Dzogchen are all the same. The length of time it takes to gain that realization is what makes the distinction.

Your concept of ka dag is a bit limited though. Kadag is not simply emptiness, though it has been dumbed down in that way for people like you."

And in response to someone asking whether Dzogchen’s uniqueness is basically tögal:

"There are a number of things which make Dzogchen distinct, thögal is one, but there are others, the explanation of the generic basis is another, the specific preliminary practices related to thögal such as 'khor 'das ru shan and so on are others, and the general requirement for some kind of introduction either through the fourth empowerment of Mahāyoga, the ati yoga empowerment found in Anuyoga or the empowerment of the potentiality of vidyā.

As far as tregchö goes, there is really no difference between tregchö, Kagyu Mahāmudra and the meditation the view of the inseparability of samsara and nirvana — all three have the same point and all three depend on the experiential view imparted during empowerment.

I also want to point out that like the rest of Vajrayāna, Dzogchen practice, path and realization completely depends on the Guru. Guru Yoga is absolutely central to Dzogchen. Without guru yoga and devotion to a realized master, no progress at all is possible in Dzogchen, none whatsoever."

Dzogchen — how to sample it and where to go deeper

Next, register interest and attend live teaching:

• Contact page: https://www.zangthal.com/contact — register your interest and ask to be notified of the next online teaching with Ācārya Malcolm Smith.

• Important: Dzogchen cannot be learned from books alone. One needs direct introduction (pointing out) and ongoing instructions from a qualified teacher. Make it a priority to receive introduction from Malcolm when a teaching is available. Sangha portals:

• Main site: https://www.zangthal.com/

• Forum: https://forum.zangthal.com/ — you may need to request access. In practice, it helps to express interest in attending Malcolm’s teachings first, then request forum access as directed by the sangha guidelines. | Dependent origination is the apparent origination of entities that seem to manifest in dependence on causes and conditions. But as Nāgārjuna states above, those causes and conditions are actually the ignorance which afflicts the mindstream, and the conditions of grasping, mine-making and I-making which are the drivers of karmic activity that serve to reify the delusion of a self, or a self ... www.awakeningtoreality.com |

Intro talk (to get a feel for Malcolm’s style):

| the future does not exist. Appearing in the present does not exist in any way. Karma does not exist. Traces do not exist. Ignorance does not exist. Mind does not exist. Intellect does not exist. Wisdom does not exist. Saṃsāra does not exist. Nirvāṇa does not exist. Not even vidyā (rig pa) itself exists. Not even the appearances of pristine consciousness exist. All those arose from a ... www.awakeningtoreality.com |

Short reading (view clarifications):

Mahāmudrā — my recommended teacher & books

For Mahāmudrā, I’ve long appreciated Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche. All of his books are clear, practical, and deeply supportive for Mahāmudrā students.

If you want one place to begin, pick one Mahāmudrā book by Thrangu Rinpoche and work through it slowly while cross-checking view in practice.

Other teachers & sanghas you might appreciate

White Wind Zen Community's Long-distance Training Program was established in 1995 to support the practice of students living more than an hour's commuting distance from Dainen-ji, the monastery founded by Ven. Anzan Hoshin roshi, located in Ottawa, Canada. Since that time, people living all over the world have joined the Sangha of students studying and practicing under the direction of Roshi's ... wwzc.org |

Open Microsoft Edge or Adobe Acrobat Reader. Open the PDF file. In Edge, click the book with speaker icon; in Acrobat Reader, find the read-aloud option in the View menu. Select "Read Aloud" and use the controls to manage playback. Adjust reading speed and voice in "Voice options." Stop the reading with the "X" button in the control bar. www.awakeningtoreality.com |

| The course features teachings by the Abbey’s abbess, Ven. Thubten Chodron. Videos and commentaries by her teachers are also included: H.H. the Dalai Lama, Khensur Jampa Tegchok, Kyabje Zopa Rinpoche, Geshe Sonam Rinchen, and others. Course facilitators include monastics, monastic trainees, and long-term students who have progressed through the SAFE program. This PDF lists the books you will ... sravastiabbey.org |

Finding a good, awakened teacher (why it matters)

If Dzogchen feels like home after a couple of months, contact Zangthal, receive introduction from Malcolm, and practice with guidance. If Mahāmudrā pulls you in, Thrangu Rinpoche’s books remain a superb self-study foundation. (Finding a good and accessible Mahamudra teacher is also important)

Happy to compare the “feel” of Dzogchen vs. Mahāmudrā in practice terms as you go—just let me know what’s landing and what isn’t.

Warmly,

Soh

Update 3rd September:

This is for those interested in Mahāmudrā:

Why I Recommend H.E. the 12th Zurmang Gharwang Rinpoche (and a new 5-year course you can join)

A while back I shared how much I enjoyed Mahamudrā: A Practical Guide and recommended its author, H.E. the 12th Zurmang Gharwang Rinpoche. That post also noted his public transmission of the Concise Commentary on the Ocean of Definitive Meaning—the root text Rinpoche elucidates in the book. (Awakening to Reality)

Who he is (in brief)

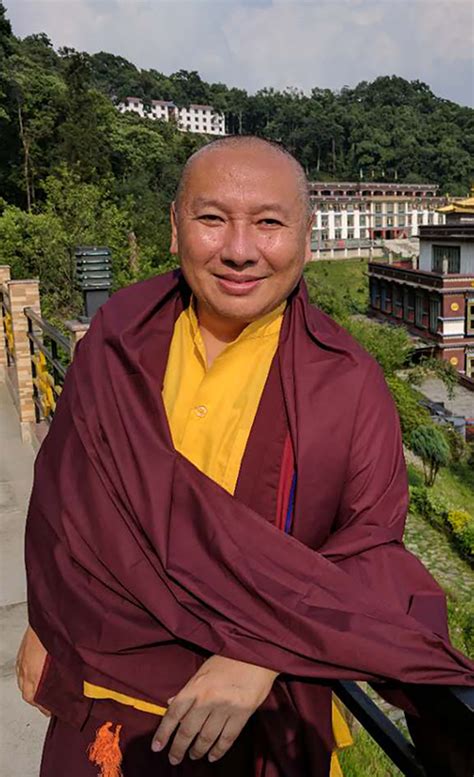

Zurmang Gharwang Rinpoche is the head of the Zurmang Kagyu school and the supreme lineage holder of its “Whispered Lineage.” He was born into the Sikkimese royal family and was recognized by H.H. the 16th Karmapa as the 12th Gharwang tulku. (The Wisdom Experience)

Why his Mahāmudrā book stands out

Rinpoche’s book is a clear, practice-ready manual that walks you from preliminaries through śamatha and vipaśyanā to the fruition. As H.H. Sakya Trichen notes in the foreword, it’s “a definitive manual” for aspiring Mahāmudrā students. You can find the book via Wisdom/Simon & Schuster or Amazon. (The Wisdom Experience, Simon & Schuster, Amazon)

-

Wisdom listing (with foreword note and description)

-

Simon & Schuster publisher page

-

Amazon product page (print/ebook)

New: Zurmang Kagyu Five-Year Program

I recently discovered that Rinpoche is offering a structured, five-year online curriculum in the Zurmang tradition. It’s designed for serious students who want steady study-and-practice under Rinpoche’s guidance. Access is currently listed at US$21 for 30 days, with free previews available. (Zurmang Kagyu)

What’s inside (snapshot):

-

Three core tracks: Bodhisattva Module, Vajrayāna Module, and Mahāmudrā Module (multi-year progression with teaching videos, readings, and guided sessions). (Zurmang Kagyu)

-

Live components: recurring teaching & meditation Zoom sessions and Monthly Q&A entries (archived by month). (Zurmang Kagyu)

-

Language support: a growing set of Chinese-language lessons alongside the English track. (Zurmang Kagyu)

-

Daily practice resources: a “Zurmang Daily Practices” section and lineage materials. (Zurmang Kagyu)

👉 Enroll or preview here: Zurmang Kagyu Five-Year Program (Thinkific). (Zurmang Kagyu)

How this fits with the book

The curriculum dovetails nicely with the Mahāmudrā manual: study the chapters, then use the course’s stepwise modules and Q&A to clarify view and deepen meditation. For context on the root text transmission I shared previously, see my earlier note on the Concise Commentary on the Ocean of Definitive Meaning. (Awakening to Reality, The Wisdom Experience)

If you’re considering joining

-

Who benefits: practitioners wanting a Kagyu Mahāmudrā path with consistent structure, feedback, and community touchpoints.

-

How to approach: pair reading (Mahamudrā: A Practical Guide) with the corresponding module lessons; keep a practice journal; bring questions to the Q&As. (The Wisdom Experience)

Links & references